Material Meditations

Proposals for creating and owning clothes in our material past, present, and future.

Senior Thesis (Fall 2021-Spring 2022).

Atacama desert, Chile, which has become a destination for garment disposal for the fast fashion industry.

Photographed by Argentine journalist Jason Mayne.

Photographed by Argentine journalist Jason Mayne.

The apparel industry struggles with sustainability and ethics at almost every step in the process.

From the production of raw materials, whether they be petroleum-based synthetics (non-biodegradable and shed microplastics) or resource-intensive natural fibers, to the massive disposal of garments in landfills. The industry is responsible for staggering amounts of environmental destruction (water pollution, land degradation, carbon emission) and social injustice (child labor, sweatshops, hazardous work conditions).

The proposals in this collection seek to begin to address these failures in the system by questioning everything from the origins of our fibers to the archetypal forms of our garments to the process of manufacturing and the end life cycle. Based on the timescale and material origins of the proposals they have been loosely categorized into three categories, Past, Present, and Future.

Past repurposes existing textiles.

Present utilizes available sustainable fabrics and design solutions that increase wear.

Future uses mycelium, the vegetative structure of a mushroom, to upcycle waste from the apparel industry.

While the garments are separated into three categories, they are meant to be styled with one another, demonstrating how these solutions can and should interact and coexist.

Special attention was also given to the design of the garments and how they can be made to fit beautifully on a multitude of bodies. A sustainable solution created without keeping people in mind, what they would want to feel and wear, will never be able to have a meaningful impact.

No single innovation will resolve all of the industry’s problems. These proposals are meant to be a beginning point for the kinds of solutions that could be implemented to move towards a better future—where the clothes we wear uplift the earth and people who made them.

PAST

It is estimated that every second, a garbage truck's worth of clothing is burnt or buried in a landfill. Only 13% of textiles from the apparel industry get recycled. This low rate results from the lack of recycling infrastructure, the high cost of recycling textiles, and our current inability to effectively recycle blended fibers. Second-hand shops have been one answer to this problem, but they also come with a myriad of issues—for instance, the huge volumes of cheap disposable clothing they are given are also frequently bundled and resold to developing countries where they flood and destroy local markets. Downcycling—tearing up garments to form loose fibers that can be used for stuffing or insulation—is another solution. However, this process results in the loss of the labor, time, material, and energy that is invested in the creation of each piece.

The goal of Past is to give new life to old pieces, keeping them out of the landfill and second-hand shop a little longer, and preserving the resources that have already been invested in them.

In order to make this approach scalable and non-labor intensive, the proposal focuses on finding a garment that was common, reasonably consistent in features, and able to be altered with a few simple cuts.

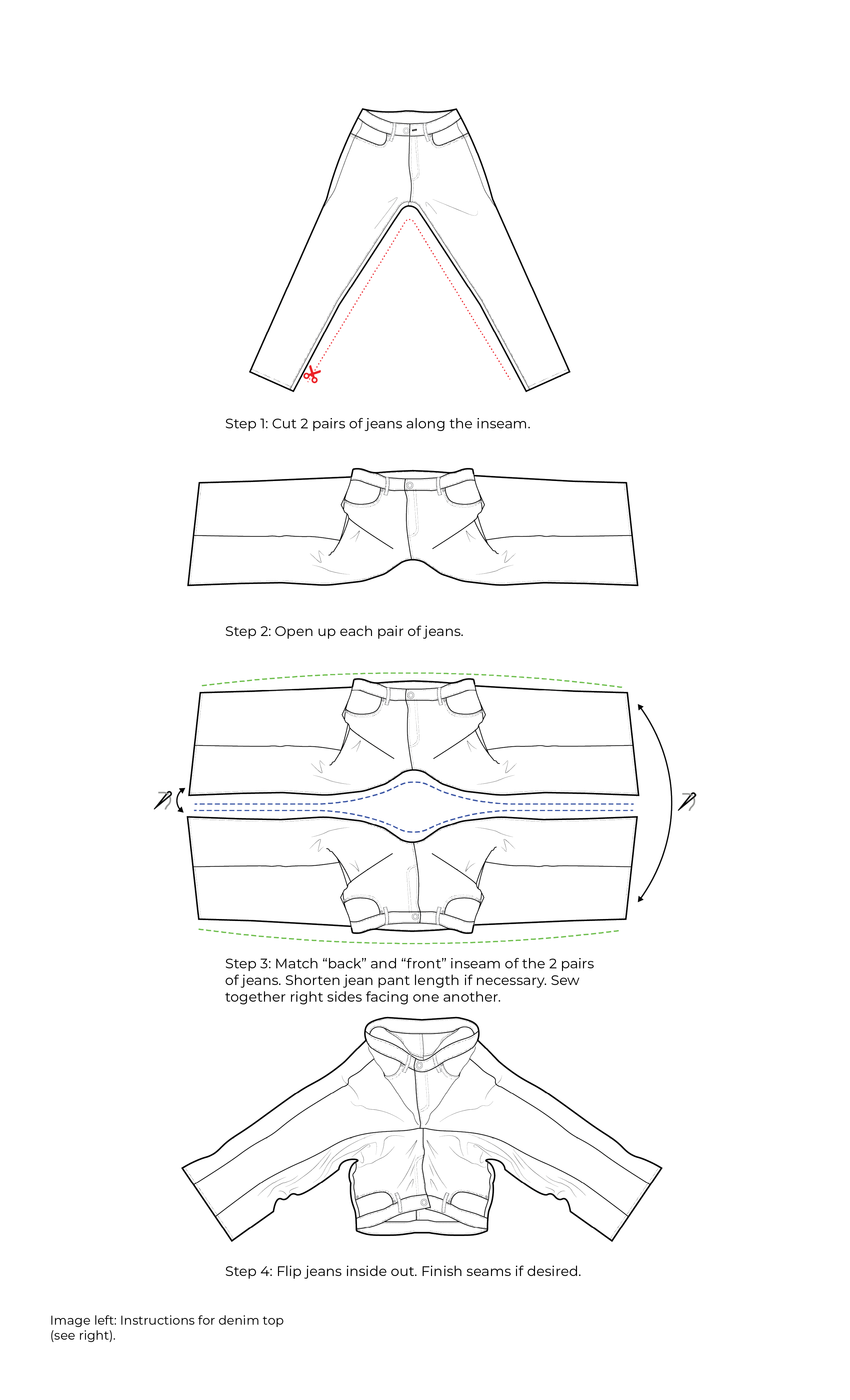

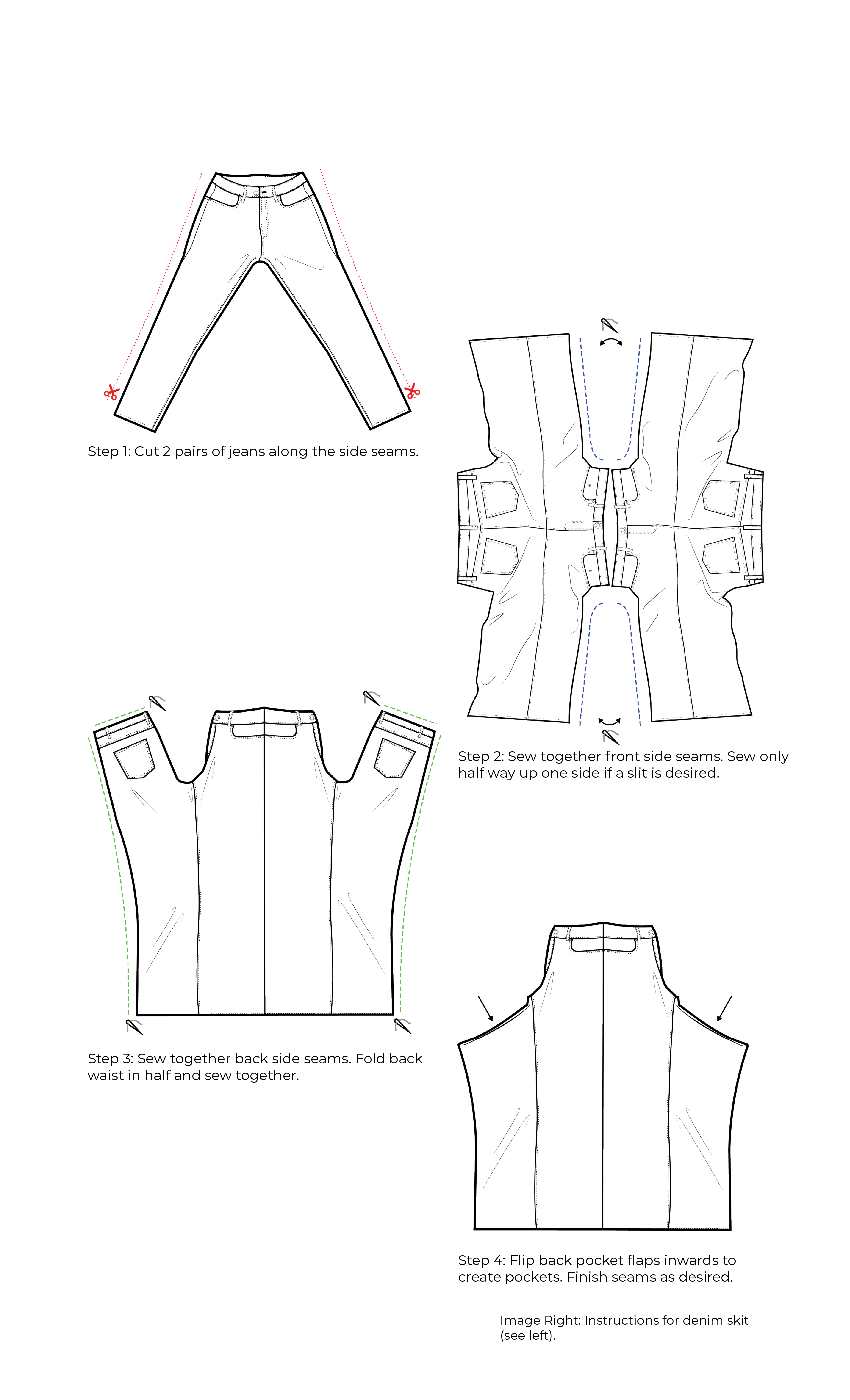

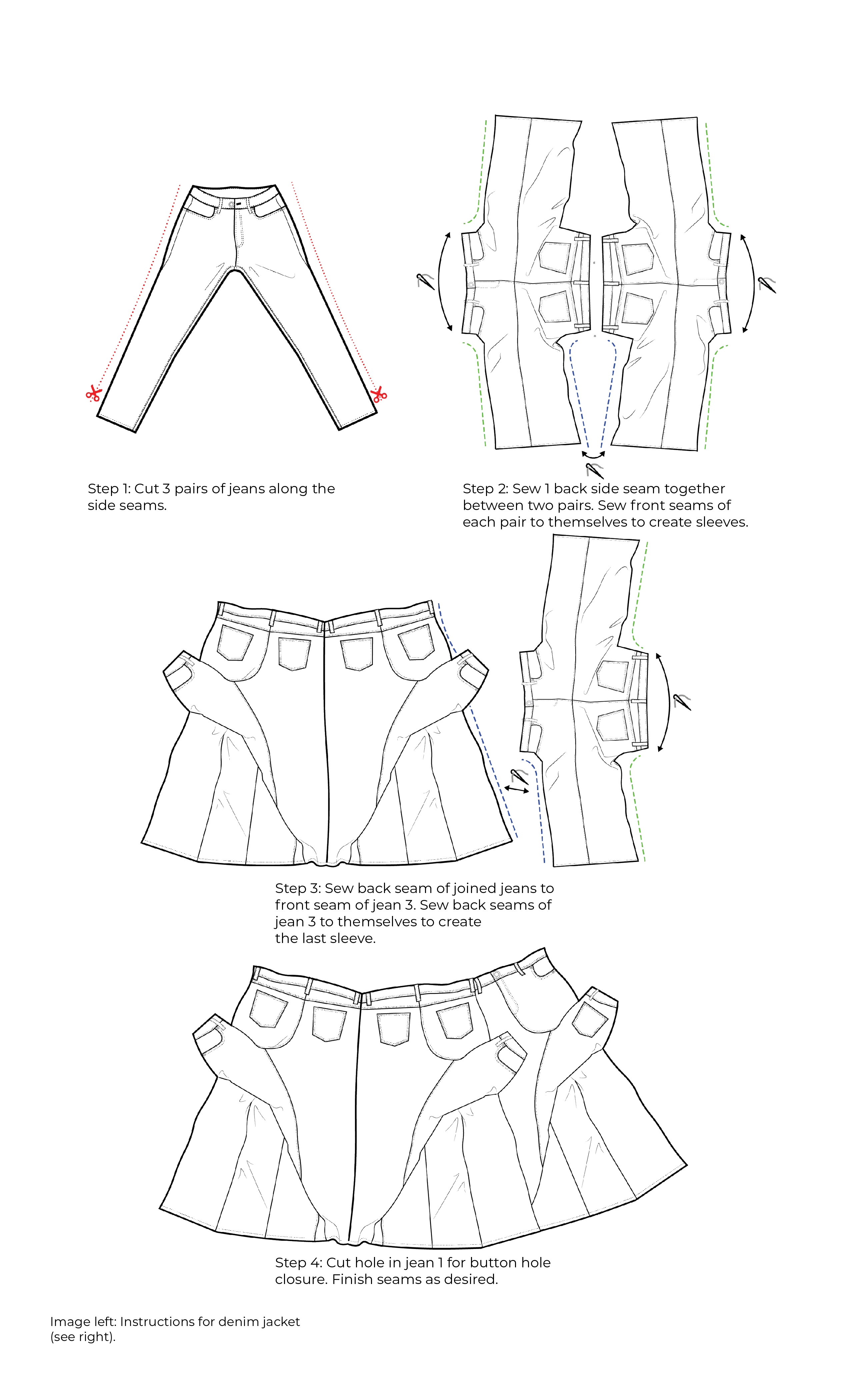

The answer was found in Jeans, which are a ubiquitous sign of the present. Using just 1 or 2 simple cuts, a simple pair of jeans can be transformed into a multitude of entirely new forms. This approach could be part of a company’s buy-back program or a simple DIY project through free patterns and instructions.

Past sketches and drapes.

PRESENT

The proposals in this section largely revolve around garments that can transform into other garments and be styled in a multitude of different ways, challenging conventional notions of the forms our garments need to take. By making the garments more versatile, this extends the lifespan of the garments and cuts back on the urge to purchase more.

The transformation and modification strategies utilize only ties made from the same fabric for fastenings. Ties were utilized as a means of making the garment adjustable to different sizes and configurations, meaning the garment can change with a person during their life and be worn over and under other garments. In addition, using no additional materials for fastenings, such as buttons or zippers, makes the garment easier to recycle at its eventual end of life.

These garments were first designed with CLO, a 3D modeling software for apparel. Utilizing 3D modeling enables the creation of a first prototype of a garment with less waste production.

These garments are also made from materials like Hemp, a fiber that grows prolifically and needs much less water than more traditional fiber crops like cotton.

Muslin for transforming garment. 'Top' and 'bottom' are identical pieces. Right two images show the piece worn with the 'hem' as the neckline.

Left two images show the piece worn with the 'waistline' as the neckline.’

Left two images show the piece worn with the 'waistline' as the neckline.’

FUTURE

Future requires a fundamental rethinking of the current apparel system and thus operates on a longer timescale. These proposals largely center around biomaterials, with the focus of this collection being mycelium, the vegetative structure of a mushroom.

The apparel industry produces a huge amount of textile waste. There is the post-consumer waste that is familiar to most people–the garments that fill landfills worldwide. But there are also large quantities of pre-consumer waste. Examples include cut-offs created during garment construction, headers and swatches provided to designers, and prototypes generated during the design process.

As mentioned earlier, these end products are difficult to recycle because of the lack of infrastructure and a current absence of technology around recycling blended fibers.

Mycelium is a potential solution to this problem, as it has the ability to break down almost any carbon-based material. Old garments and waste fabric scraps produced in the garment industry are upcycled into a new fabric by having the mycelium consume and bind the scraps together. The end product, dubbed Mycoweave, is a leather-like fabric that can be grown in different shapes and sizes. The process is circular because old Mycoweave can be upcycled by feeding it to a new batch of mycelium.

See more about the process of Mycoweave.

Mycelium grown on fabric scraps. Grown for 4 weeks. Pressed while drying. Autoclaved for 45 minutes and plasticized with glycerine.

Mycelium grown on fabric scraps. Grown for 4 weeks. Pressed while drying. Autoclaved for 45 minutes and plasticized with glycerine.

Mycelium grown on fabric headers. Grown for 1 week. Pressed while drying. Baked for 30 minutes at 200 °F. Pressure cooked for 10 minutes and plasticized with glycerine.

Mycelium grown on fabric headers. Grown for 1 week. Pressed while drying. Baked for 30 minutes at 200 °F. Pressure cooked for 10 minutes and plasticized with glycerine.